I have this idea that photography is a complex, not very clear language. The idea reflects the constant renewal of the vocabulary of imagery, which is replenished and evolves with daily updates, from contemporary culture, visions and technology. Italo Zannier says that photography is not a technique. It’s an ideology. According to Brassai, photography should suggest and not insist or explain. And, lastly, the great Eugene Smith used to say: “Let truth be the prejudice.”

On these grounds, I naturally began to look at Carlo Carletti’s photographs with the prejudice that I have always had as regards the genre disciplines, convinced that they impose limits on creativity. Then I met the photographer, I listened to his words, his reasons. I sensed his capacity to convey an awareness and outline a different context from that which I had initially perceived for ceremonial photographs.

“I’ve always felt” – says Carletti – “a strong attraction to the Barthesian themes of the spatial- temporal double in photography. But this means the past is re-presented insofar as ‘it was’, but always framed in the present.

Photography doesn’t recall something else, but in some indecipherable way is that very thing.

This mystery of the present memory is undoubtedly what fascinates me most in photography and photographs. The rest is in

any case secondary: beautiful or ugly, the genre, models and styles.”

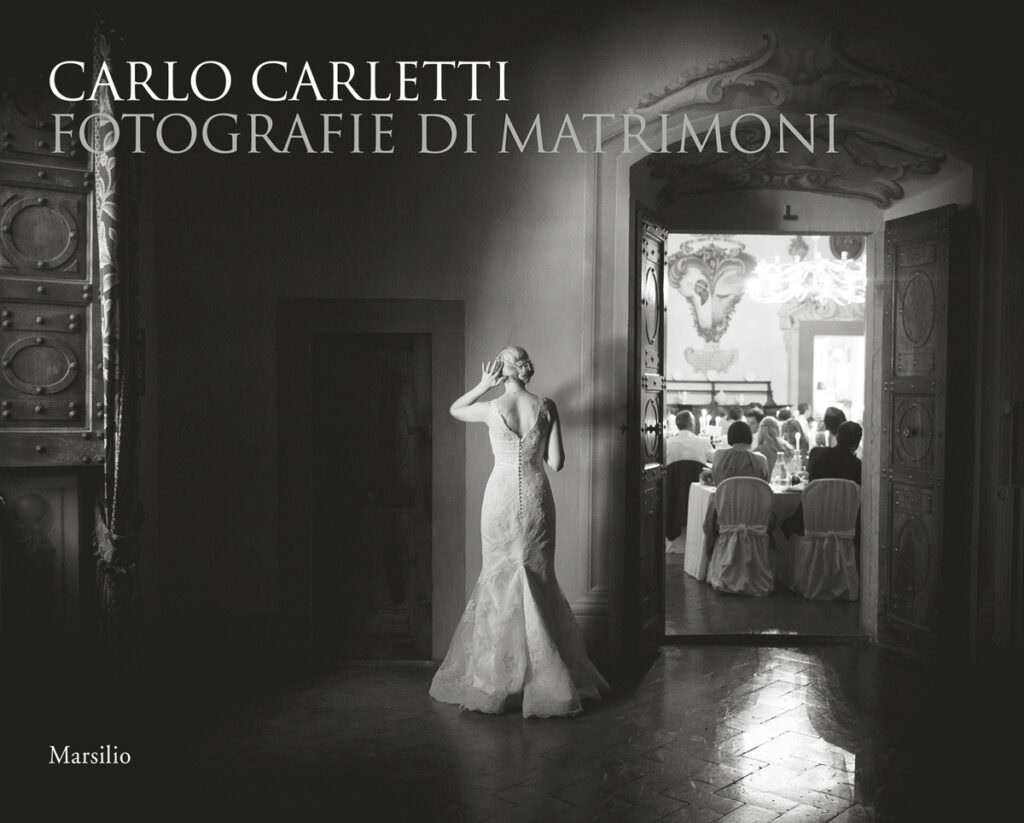

On hearing these words, my prejudice was pushed to the background and these photographs reveal a way of looking that is capable of narrating. Of gathering scattered feelings. Of ordering emotions. Of restoring the sense of one and several stories, together with reflections on photography and its persistent memory. In fact in Carletti’s thoughts and images the reference to Roland Barthes’ concept of relique to explain photography as a symbol and sign of the inexorable dissolving action of time clearly emerges and is more comprehensible within his personal creative context. A wedding, the most exciting day, the event intensely dreamed of and longed for in the life of a couple, provides a typical illustration of this concept. On these premises, the photographer pursues the dreams and desires of the people portrayed so as to stage their feelings and sentiments in a unique narrative, which goes beyond simple documentation. The scenes in his photographs – consisting of gazes, poses and expressions – capture unrepeatable moments so that they will never be forgotten and they will always be kept in the only place possible, the place of images, in which the signs of time become indelible and enduring. In this sense Carletti’s photographs successfully express a memory, in a narrative sequence in which the photographer explores people’s own desires to be represented.

The poetics of the photographic stage-setting thus open up to the concept of the “candid camera”: an approach – a combination of style and research – that explores the depths of the portrayed persons’ feelings in order to translate their purest and innermost expressions. The self- awareness of the gaze behind the lens reveals the complicity of a shared action, involving the photographer and the protagonists in the scene, through an emotional process for which photography is the most spontaneous expressive means.

What attracts me most in Carletti’s photography is his awareness of vision: this makes him an artist in the world of photography and specifically in that of ceremonial photography.

His style is neither static nor standardised, but narrative and expressive, thanks to the aesthetics concealed in the naturalness of the poses and the spontaneous nature of the actions. Shot after shot, the sequences of Carletti’s images immortalise a present moment in the very act of becoming past. All of this provides the photographer with the indispensable inspiration for the construction of highly effective stage sets and compositional solutions, in which the people move easily and wish to leave immemorial traces of such a spellbinding moment.

At the end of his own thoughts on the subject, Carletti highlights the close relationship between reality and representation which in photography finds the space to generate new contexts and collective images, to the background of a carefully chosen memory and a vivid present:

“If I did not reprogramme mentally this posthumous effect with the best imaginary result possible in the photographs that I take, I wouldn’t care at all about photography itself.”

In Carletti’s words I rediscovered the poetics of images underlying all narratives, poetics based on the ambiguity and specificity of the photographic medium.

Ultimately, the key for understanding “the most marvellous invention” has always lain in interpreting reality. This has led to the multifaceted power of photographic language, which can portray an inner essence, a feeling and an emotion only through a self-conscious willingness to generate non-mirror images with which the subject of the vision can identify as the author – like the photographer – of the creative act.

Denis Curti